The 1983 Feldman BOTCH rule was the event that, beginning 40 years ago, crippled our Bill of Rights and essentially destroyed due process and property rights. The 1983 Feldman Sup Ct decision omitted the word HIGHEST on page 464 of the decision. They ASSUMED that readers understood that the rule pertained to the 50 States' HIGHEST courts (supreme courts), when they wrote "like the judgments of state [HIGHEST] courts (I'm adding HIGHEST). I particularly emphasize ASSUMED because real-world problem-solvers "throw out all assumptions" when they have a thorny problem and have "to go back to square one" to try to figure out what's going on. They know from years of experience—over which time they often enough "got bit in the butt" by some assumption they unwittingly made—that they must be punctilious in their "root cause analysis."

The 1983 Feldman Sup Ct decision actually meant ONLY a state's HIGHEST (supreme) court. as explained further, below, but it's very simple: the decision was not including state trial courts and intermediate appeals courts (a state's lower courts). This is obvious to anyone who actually reads the first two pages of the decision: that the Feldman rule came from the #1257 statute (Congress' law), which mentions ONLY TWO courts—the US Sup Ct and the sup cts of the 50 states. The #1257 statute (and thus the Feldman rule) does NOT pertain to lower state-courts. This explanation ("rambling screed") is quite repetitive because I have to drive the point home as many times and in as many ways as possible; no one can believe (and the media won't admit that they've missed this for 40 years) that "learn-ed lawyers" and "widely-respected jurists" didn't see this over 33 years—until the 4th Circuit federal appeals court saw it in 2014; and two years later, the 1st Circuit did. Bill Foster the Illinois Congressman and Fermilab/Harvard-physics-PhD said: "It’s necessary to repeat your fundamental message again, and again, and again...And you say that again and again until it makes you queasy." I'm going to lean on him about the Feldman BOTCH and introducing a bill to fix it.

Real-world problem solvers (plumbers, electricians, HVAC, auto-repair techs, truckers, farmers, engineers, etc, who make, transport, install, and fix stuff you need) draw a diagram to show their coworkers and bosses and themselves when they want to be as clear as possible about the problem they are working on. We engineers and other real-world problem solvers want advice from our coworkers and bosses—whom we know are sharp and supersharp because we're always discussing things and helping each other work things out. A diagram essentially eliminates ambiguity. This discussion process, when there's a meeting with a board or screen on which to draw and display diagrams, is frequently called an engineering design review. But all real-world problem solvers do the same thing, regardless of what they call this brainstorming process. We want our bosses to know what we're doing, so if we're wrong, we don't lose our jobs. Judges essentially NEVER lose their jobs. When they screw up and cripple our Bill of Rights, as they did in Feldman, it's kept hidden by their baloney mumbo-jumbo, which is swallowed by the media that automatically use jargon such as "widely respected jurist," even they they are total idiots. This is an anti-corruption project focused on the courts. It begins with an exposé of judge incompetence and corruption. There will be a REAL debate outside of the Baloney Respectfully courtrooms, if the lawyer-mob dares to.

Real-world, physical-world problem solvers draw a diagram when they want to show their fellow-workers and boss what they've discovered. Whether it's under the hood or in an HVAC crawl space or any other place that real-world "thing" is, they want to fix the thing, and they want to get different views on what they've seen and measured; and what other theories might be for what's wrong with the thing and how to fix it. This is called teamwork. Also called an engineering design review. We physical-world problem-solvers want to keep our jobs because we like our jobs. So a diagram makes things as clear as we can because we want the smart people at work to bring their knowledge and insights to bear. They've helped us previously, and we've helped them, too. A-hole lawyers and judges might want to know that this is actually fun and satisfying: to have real knowledge and skills and a job where being right matters...unlike the snotty megalomaniac judges who can't pass jr high math quizzes and spend their sick lives writing zingers when they're flat wrong. BTW, I may have forgotten to mention that I'm pissed off, and you should be too because these incompetents have stolen our country.

Lawyers and judges don't draw diagrams. Maybe they think a diagram is beneath them, I would guess, based on their attitudes. They think they can write words that pinpoint precisely everything about a problem and a solution. This is utter nonsense (I'm restraining my word-choice), and I have a compendium of judge-decision evidence on this. There is no substitute for a diagram to put the clearest-possible picture in the mind of a reader or listener. Then math to use the best tools for objective analysis that humans have invented. Imagine trying to engineer and build any real-world thing you need by using words, alone. That these judge-buffoons would even think that, in modern times, they could avoid modern tools of objectivity—math—and use words alone to describe our (former, now crippled) Bill of Rights, shows what small-minded creatures they are. All the while they blow their gasbag verbiage about "objectivity" and the "rule of law."

Below are two diagrams that show the root cause of why George Floyd was killed (out-of-control courts giving bad cops the Anything Goes signal), and of every major US domestic problem. But I want to insert a note on what I've mentioned once before, and I'll say more later: that from what I know and saw. Officer Tou Thao maybe should have gotten 7 days community service—maybe. He did nothing wrong, objectively.

I don't know how many other lives, in addition to Mr. Floyd's, have been ruined or terminated by the 1983 Feldman BOTCH, and I don't want to guess, but a great many.

The BOTCH was the omission of one word: HIGHEST, in Feldman's referring to Congress' #1257 law, which mentions only: 1) the HIGHEST court in a State; and 2) the US Sup Ct. No other court is mentioned in #1257. Brennan and his clerks (who wrote Feldman) were incompetent. But supposedly 7 other judges and their clerks read it because they "concurred." Stevens "dissented," and was part of the way there, in a sense, but he didn't see it. In 2005, the Exxon case (written by Ginsburg and her clerks) actually reversed the BOTCH, but she partly screwed up and left the bad Feldman phrase in there. Nevertheless, there was enough there—and certainly in the intervening 22 years, so that any real reader (and lawyers and judges have their cerebra so far up there collective assinus—Latin for heads where the moon don't shine—that they can't see anything) could see it easily. But lawyers and judges could not. Yes, I'm really pissed, and we're going to have a REAL debate, Juris Dorkuses. You don't have a clue how real-world problem solvers think because you can't find a dipstick under a hood. You haven't come near a real world problem in decades, if ever...where right and wrong can be objectively-determined.

The key phrase was "judgments of state courts," which should have been, "judgments of HIGHEST state courts" or "judgments of state HIGHEST courts," either one would make the point that the Feldman rule applies only to a state's supreme court. Brennan and the others assumed that everyone understood that they were referring to the HIGHEST state court and not all state courts. Real-world problem-solvers know that they must "throw out all assumptions" when they have a thorny problem. Everything must be double and triple checked, and you try really hard to find something you might be missing. They know this because they've been bitten in the butt enough times over the years by some assumption they made. Lawyers and judges, including Supreme Court judges, don't know this or anything else about real-world problem solving—or even about abstract problem-solving. They just assumed that everyone could see that HIGHEST was understood (because #1257 referred only to "HIGHEST court in a state"), but that assumption has led to disaster. Again, real-world problem solvers have learned from hard-experience that you cannot assume that your words alone are understood. YOU MUST DRAW A DIAGRAM..

A great many lives have been ruined or terminated because of these Supreme Idiots. Now, about the diagrams.

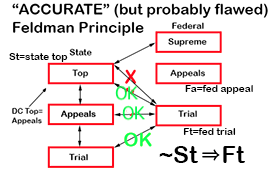

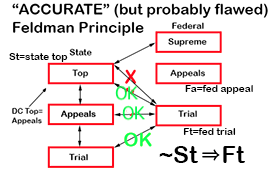

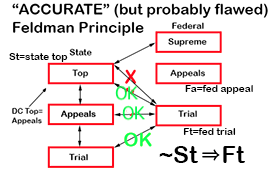

The first diagram shows the Feldman rule blocking a case from going from the FINAL DECISION OF A HIGHEST state court to a federal trial court. (A pre-final decision of a state supreme court—such as a ruling on a motion—could go to a federal trial court, but this is very unlikely to occur.) This is the CORRECT Feldman rule. The green OKs mean it's OK to take a case from a lower state court to a federal trial court.

Congress has full Article3 authority to write legislation—and include a diagram with Boolean expression (10th grade math)—and make sure that federal judges follow the correct Feldman rule, under threat of impeachment and, later, docking of their pensions. (Did you know that federal judges' salaries continue until they fall over? IDK how many "pensions" equal the working salary.)

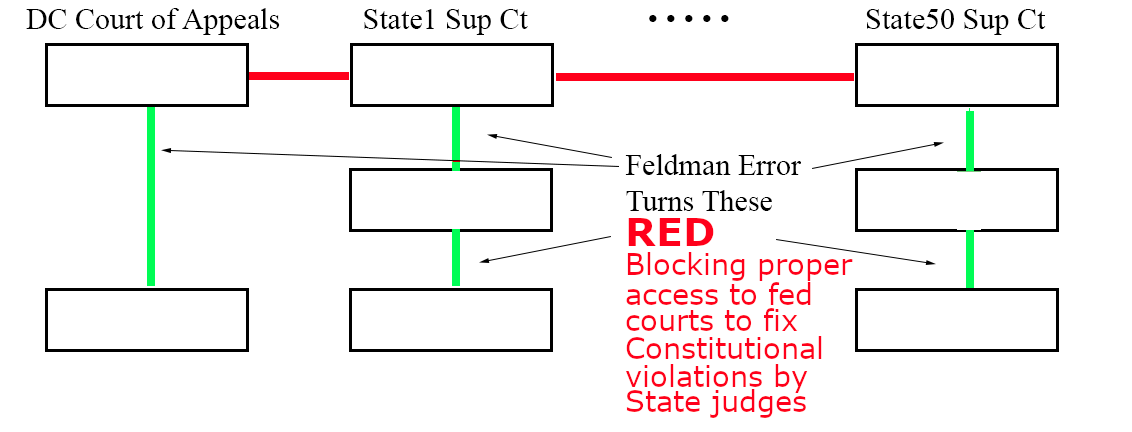

The second diagram shows the hierarchy of state courts. All states have a top, supreme court and trial courts at the bottom. They may all have intermediate appeal courts in the middle; IDK for sure. The top horizontal line (RED) means that all state top courts are treated the same way: that once you've gotten a final decision from a state's top court, you are blocked from going to federal trial court. The only place you can take that decision is to the US Supreme Court, where your chances of getting heard are nil, even if you pay $200K for lawyers and the royal trappings like special booklets for the Supreme judges who don't want to risk getting poked by a staple; but to repeat, they can't pass 8th grade math quizzes.

My diagram note says that Feldman turns the vertical lines going down the state-court hierarchy RED. That means that the BOTCH prevents you from taking (to a federal trial court) any decision from any state court lower than the state top court. The correct Feldman rule DOES allow you to take those lower state-court decisions to federal trial court. The Feldman BOTCH incorrectly stops you from taking lower-state-court decision to federal trial court.

This is the root cause of why state-court judges do WhateverTF they want. Of course there's no accountability for federal judges, either, and that's why you shouldn't be electing lawyers to Congress. They are obsessed with the Baloney Respectfully — little kids playing the umbrellastepping playground game where what counts is "formal talk" and kissing the butt of a judge. Substance—right and wrong—doesn't count. Just the kach$ng of lawyer fees. I repeat: we're gonna have a REAL debate on this, and I will slap down their playground name-calling in ways they never imagined. To real-world problem-solvers: I'm quite sure that you've been highly skeptical of lawyer mumbo-jumbo that you suspect is garbage. You've been right. You know how to cut through the crap. That's what this project is about.

4. The “accurate” (non-MISTAKEN) Feldman rule allows a litigant to challenge, in federal district court, any ruling (Fig 1, green Oks; see color page attached to end of Complaint) except the final decision from a state’s highest court, which must go to the US Supreme Court, according to the rule. (This is not actually true because §1257 states, “may,” but it is not worth arguing about since violations by lower state judges are by far the biggest issue, and a litigant usually has time to file in federal court, before a state’s highest court decides anything. So placing the Feldman bar to state, highest-court decisions does not bar any practical case; a plaintiff can begin and pursue his federal-district case so long as he files before any state highest-court decision.)

5. The Fig. 2 green line (see color page attached) shows the “narrow,” limited applicability of the accurate Feldman rule, with the red lines showing that the CORRECT, narrow-Feldman rule does not block a federal court from correcting lower state-court federal-question errors. The red lines stop the carnage wreaked by Feldman BROADLY AND WRONGLY reaching down to block lower state-court decisions from challenge in federal court. This carnage took George Floyd, among many others, as police who are inclined towards bad behavior (the minority of police) see judges bail out their extortionist lawyer-pals, as Berman saw on glaring display in Minneapolis in the months preceding Mr. Floyd. Six weeks before Mr. Floyd, Berman petitioned the Minnesota Supreme Court and stated that there was a “military regime” operating in Hennepin County. The Feldman MISTAKEN rule erroneously applies the Feldman bar to lower state-court decisions and turns the red lines green in Fig. 2, allowing the Feldman poison to flow down and kill the 14th Amendment’s path from lower state courts to federal district court to enforce “restrictions of State power” abuses (ex parte Virginia 346, where a Virginia federal judge put a state judge in jail for failing to abide by federal law prohibiting discriminatory practices keeping blacks off of juries) by lower state courts. Under the Feldman MISTAKEN rule, that Virginia state judge would have been allowed to continue excluding blacks from juries. In modern times, the path to the US Supreme Court is effectively impossible. Had Feldman been decided in 1883 instead of 1983, an additional century of its havoc would have ended the Bill of Rights entirely, whereas now the Bill of Rights is on its last legs after only 40 years; but no leg was able to save Mr. Floyd from the knee on his neck.

6. The Boolean expression in Fig. 1 is the formal-logic expression of the

simple and accurate Feldman rule ‾ST→Ft ; if a litigant has not received a final

decision, ST, from a state’s Top court, then the litigant can file in a federal trial court, Ft to challenge the state judge’s federal violation. (The first subscript is changed slightly from the diagram: capital “T” for Top court to distinguish from lower-case “t” for trial court.) Well-defined Boolean expressions are objective and remove the wordplay and “sidestepping” of the law that goes on in courts nearly all the time. Congress must include Booleans in legislation -- and append them to decisions such as Feldman to make sure that federal judges have a simple and objective statement of Congress’ intent. This can be done under Congress’ Article III authority to “regulate” the lower federal courts through the Supreme Court’s “appellate jurisdiction.” As noted, Plaintiff has had to pursue a political route to end the Feldman abomination, since a route through the courts is, to put it diplomatically, more difficult.

7. Asarco Inc. v. Kadish, 490 US 605, 622 (1989), makes the accurate Feldman rule as clear as can be:

The Rooker-Feldman doctrine interprets 28 U. S. C. § 1257 as ordinarily barring direct review in the lower federal courts of a decision reached by the highest state court, for such authority is vested solely in this Court. District of Columbia Court of Appeals v. Feldman, 460 U. S. 462 (1983); Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. v. Locomotive Engineers, 398 U. S. 281, 296 (1970); Rooker v. Fidelity Trust Co., 263 U. S. 413, 415-416 (1923).

(Asarco 622.)

In other words, “direct review in the lower federal courts” of “a decision reached by the highest state court” is barred, to rearrange Ascaro, slightly. There is no Feldman bar to federal-district review of a decision from a state trial or appeals court.

8. The First Circuit has the Feldman rule precisely correct: (Klimowicz v. Deutsche Bank Nat. Trust Co., 907 F. 3d 61, 65 (1st Cir. 2018) (“As long as a state-court suit has reached a point where neither party seeks further action in that suit, then "the state proceedings [are considered] ended" and the judgment is deemed sufficiently final to trigger the Rooker-Feldman doctrine. Federación de Maestros de P.R. v. Junta de Relaciones del Trabajo de P.R., 410 F.3d 17, 24 (1st Cir. 2005) (quoting Exxon Mobil, 544 U.S. at 291, 125 S.Ct. 1517))”) Otherwise, there is NO Feldman bar, so long as there is some state-court opportunity for a litigant to reverse a state-court decision.

9. The Fourth Circuit Thana v. BD. OF LICENSE COM. FOR CHARLES COUNTY, 827 F. 3d 314 (4th Cir. 2016),

“First, if we apply STRICTLY [and Exxon emphasized the ‘narrowness’ of the decision, so any ‘loose’ application would be wrong] the Supreme Court's instruction that the Rooker-Feldman doctrine is to be "confined to cases of the kind from which the doctrine acquired its name," Exxon, 544 U.S. at 284, 125 S.Ct. 1517, we would conclude that the doctrine does not [AND IT CANNOT] apply here because the district court here was not called upon to exercise appellate jurisdiction over a final judgment from "the highest court of a State in which a decision could be had," 28 U.S.C. § 1257(a) (emphasis added), as was the case in both Rooker and Feldman. In those cases, instead of seeking review in the Supreme Court of a judgment entered by the State's highest court, the losing party pursued review of the judgment in a federal district court, frustrating the Supreme Court's exclusive jurisdiction over such a [HIGHEST-COURT] judgment. See 28 U.S.C. § 1257(a) (providing that "[f]inal judgments or decrees rendered by the highest court of a State in which a decision could be had, may be reviewed by the Supreme Court" in cases raising federal questions); see also Exxon, 544 U.S. at 291, 125 S.Ct. 1517 (noting that, in both Rooker and Feldman, the plaintiff "filed suit in federal court after the state proceedings ended" (emphasis added)). Obviously, the case before us does not fit that profile.”

10. Plaintiff Berman’s action here does not fit “that profile,” either; and a “strict” application of the Feldman rule is the only correct application, as Exxon held: “the Third Circuit misperceived the narrow ground occupied by Rooker-Feldman, and consequently erred in ordering the federal action dismissed for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.” (Id. 284.) There can be no correct “loose” or “broad” interpretation of the Feldman rule. The Feldman rule is “narrow” and “strict.” It cannot be repeated often enough, from Feldman itself: “review of a final judgment of the highest judicial tribunal of a state is vested solely in the Supreme Court of the United States;” Feldman at 474. Feldman provides no actual basis for federal district courts to reject federal-question complaint’s against a state lower-court judges, prior to a state’s highest court’s final decision. (Only because of Feldman’s MISTAKEN wording -- state [HIGHEST] court judgments -- omitting HIGHEST, has the Feldman devastation persisted for four decades.) And no decision has yet come out of the California Supreme Court on this matter. makeamericageekyagain@gmail.com